Today is Pi day! On March 14th (3/14 in the American calendar), mathematicians celebrate the famous mathematical constant Pi. But what exactly is Pi? Pi is represented by the Greek letter $\pi$, and is defined as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. Why a circle? Circles are fundemental in geometry as they can be used to contruct other geometric shapes such as certain regular polygons. Moreover, many things in our universe are curved and can be described through a circular nature.

A Brief History of Pi

Pi has been a concept explored by mathematians for over 4000 years. The Ancient Babylonians from circa 2000 BC first calculated $\pi$ to be $3$. About 350 years later, the Ancient Egyptions estimated $\pi$ to be $3.16$. Later around 250 BC, the Ancient Greek mathematician, Archemides geometrically estimated $\pi$ to be bounded below $\frac{22}{7}$. Archemedes used a geometric method of inscibing a polygon inside the circle to estimate its area and then estimate $\pi$ thereafter, This method is also known as the method of exhaustion. If you want to learn more about the history of $\pi$, read The Varsity’s, A Brief History of pi ($\pi$).

The painstaking geometric methods of Archimedes hit a computational wall. Doubling polygon sides to calculate $\pi$’s digits was like trying to fill an ocean with a single water one drop at a time: progress slowed exponentially. By the 17th century, mathematicians pivoted to a new tool: infinite series.

Unlike polygons, infinite series rely on summing an endless sequence of shrinking rational numbers that collectively converge toward $\pi$. This approach, rooted in calculus, transformed $\pi$ calculation from a geometric puzzle into an algebraic art form.

Madhava-Leibniz

In the 14th-15th century, Madhava of Sangamagrama first discovered that repeatedly adding alternating recipital of odd numbers would converge to $\frac{\pi}{4}$. Later in the 17th century, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, independantly discorved the formula by taking the Taylor Series approximation of $\arctan(1)$. The Madhava-Leibniz (Leibniz) series is expressed as,

\[\frac{\pi}{4} = 1 - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} - \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{9} - \dots = \sum^\infty_{k =0}\frac{(-1)^k}{2k+1}.\]When estimating $\pi$, we must truncate the Leibniz series to iterate up to a finite value $N$. It can be rewritten as:

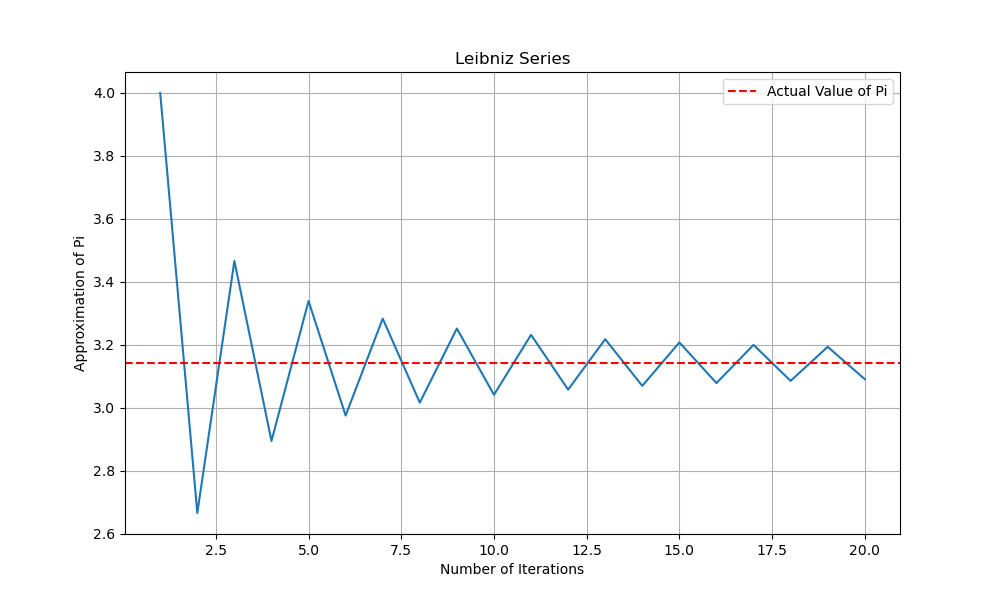

\[4\sum^{N}_{k=0}\frac{(-1)^k}{2k+1} = 4\left(1 - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} - \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{9} - \dots + \frac{1}{2N+1}\right) \approx \pi.\]Below, is a plot of the Leibniz formula computed over the number of iterations $N$, compared to the true value of $\pi$, which is estimated by mpmath.pi.

The Leibniz series converges to $\pi$ in a periodic fashion. Compared to the algorithms that follow, the Leibniz series is extremely inefficient.

Machin formula

In 1706, John Machin derived his formula for approximating $\pi$. Machin’s formula is expressed as the following,

\[\frac{\pi}{4} = 4 \arctan\left(\frac{1}{5}\right) - \arctan\left(\frac{1}{239}\right).\]Similar to Leibniz’s aproach, a Taylor series approximation of $\arctan(x)$ can be applied to make computation easier.

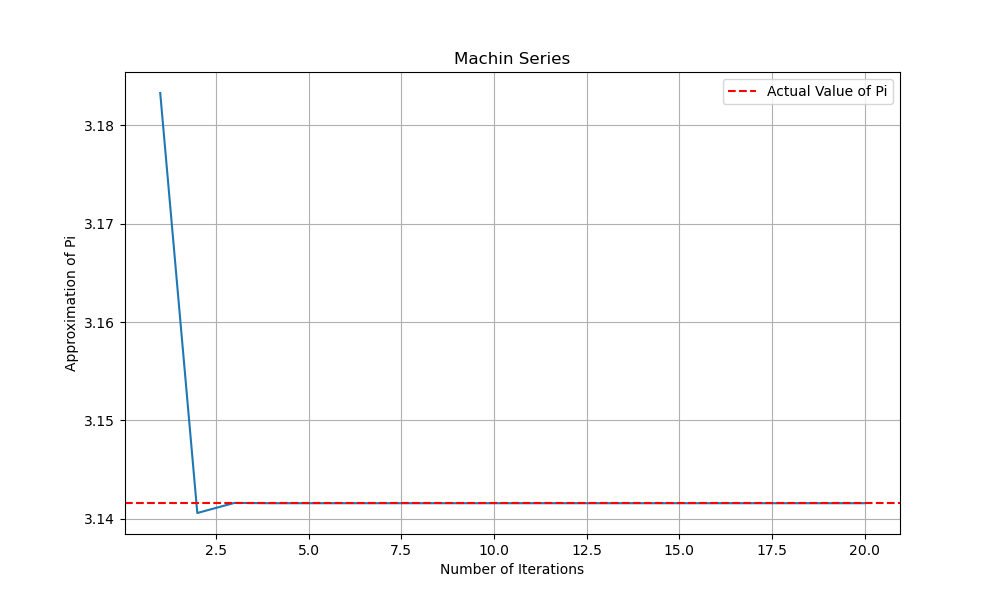

\[\arctan(x) = \sum^\infty_{k=0}\frac{(-1)^k}{2k+1}x^{2k+1} = x - \frac{x^3}{3} + \frac{x^5}{5} - \frac{x^7}{7} + \dots\]The following figure shows the convergence of Machin’s formula to mpmath value for pie $\pi$.

Machin’s formula converges to mpmath value of $\pi$ way faster than the Leibniz series. But we can do better!

Chudnovsky Algorithm

In 1988, the Chudnovsky Brothers derived an extremely fast algorithm for approximating $\pi$. The Chudnovsky algorithm was based on the Ramanujan-Sato series. The Chudnovsky algorithm is expressed as,

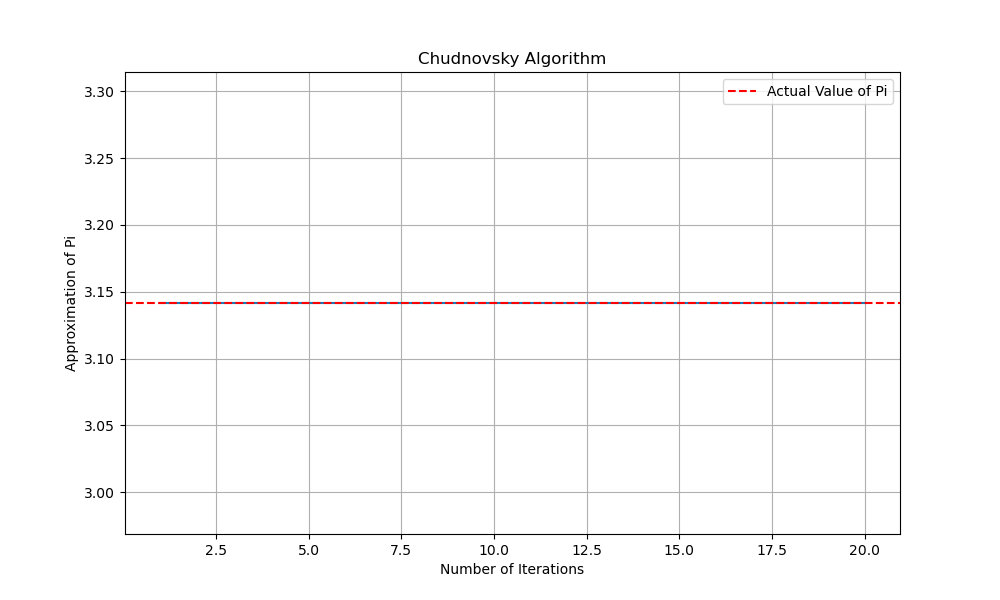

\[\frac{426880\sqrt{10005}}{\pi} = \sum^\infty_{k=0} \frac{(6k)!(545140134k+13591409)}{(3k)!(k!)^3(-262537412640768000)^k}.\]The following figure shows the convergence of Chudnovsky algorithm to mpmath value for $\pi$.

The Chudnovsky algorithm converges exetremely fast. After just one iteration, it appears to have converged on mpmath value of $\pi$. There is something elegant about this big, complicated looking series converging to a number related to circles. It’s almost like magic!

Comparision

Below are approximations of $\pi$ using the three methods described above,

Iterations 1000: Leibniz Pi Approximation: 3.14059265383979292596359650286939597045138933077972

Iterations 1000: Machin Pi Approximation: 3.14159265358979341070329540414799701489814825002874

Iterations 1000: Chudnovsky Pi Approximation: 3.14159265358973420767089413992905460809870040571094

After 1000 iteration, the Leibniz series approximates $\pi$ up to 2 decimal places. Compared to Machin’s formula and the Chudnovsky algorithm, the Leibniz series converges much slower. In terms of order of convergence and precision, the Chudnovsky algorithm is the best method to approximate $\pi$. The Chudnovsky algorithm has broken many world records in calculating digits of $\pi$, including 2.7 trillion digits in 2009, 10 trillion in 2011, 22.4 trillion in 2016, 31.4 trillion in 2018-2019, 50 trillion in 2020, 62.8 trillion in 2021, 100 trillion in 2022, 105 trillion in March 2024 (last years Pi day), and the most recent 202 trillion in June 2024.

The code used to create the figures can be found here.

Conclusion

From polygons to infinite series, calculating $\pi$ has become a testament of human curiosity and computational ingenuity. What started as a quest to measure the circumference of circles now drives our obsession with precision, pushing math and computing to their absolute limits. We’ve calculated 202 trillion digits so far, but there are still more records to be broken. Happy Pi day! 🥧🔢