Netwon’s Gravitation

In 1687, Isaac Newton published his famous Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, where he introduced the Law of Universal Gravitation. The law states that bodies exert a force on each other at a distance, and that the strength of this force decreases with the square of the distance between them, also known as an inverse square law. In other words, the further apart two bodies are, the weaker the gravitational pull between them.

However, this raised a mystery that left physicists at the time puzzled. How do the bodies know to apply a force on each other through empty space? This is sometimes called, action at a distance.

Newton was deeply uncomfortable with this “absurdity”, stating in 1692 that no one with a “competent faculty of thinking” could ever believe a body could act upon another through a vacuum without mediation. He published only the mathematical principles and purposely avoided a definitive claim on the physical “cause” of gravity. To resolve this, many scientists turned to aether theories, proposing an undetectable elastic medium that filled space and conducted forces.

Gravitational Potential

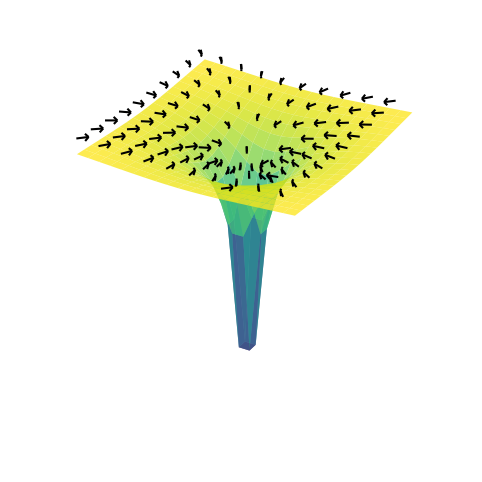

In the late 18th century, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, and independently Pierre-Simon Laplace and Adrien-Marie Legendre, introduced the concept of a gravitational potential, assigning every point in space a value representing potential energy relative to a massive body. Objects naturally move toward regions of lower potential energy. The negative gradient of this potential gives the gravitational acceleration at a point. Multiplying this acceleration by an object’s mass also yields the gravitational force, according to Newton’s second law. We can think of these as fields: a scalar potential field and a vector acceleration field. If these fields are real physical entities, they provide a natural explanation for the problem of action at a distance. The following figure illustrates a gravitational potential (colour map) and gravitational field vectors (Black) pointing toward a singularity, representing the location of the massive body:

Faraday and Magnetic Fields

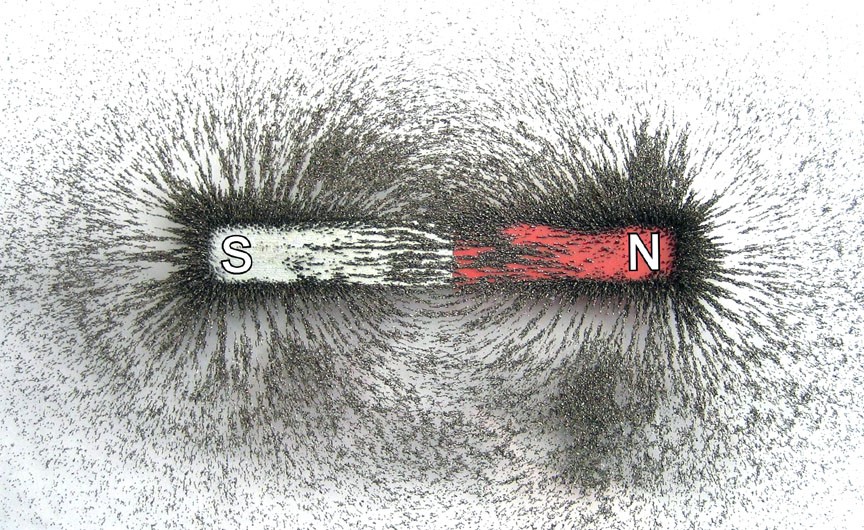

It was not until much later, the 19th century, that the term field was coined by Michael Faraday. Faraday famously used iron filings around a magnet to visualise the magnet’s magnetic field (see figure below). He used the visual evidence of the curved lines to challenge the action at a distance model: if a force was simply a direct, instantaneous link between two bodies, the lines should be straight and purely determined by the two objects. Instead, his experiments suggested that space itself carries the influence of forces.

Maxwell’s Equations

Building on Faraday’s experimental insights, James Clerk Maxwell in the mid-19th century provided the mathematical framework that formalised the concept of electromagnetic fields. Maxwell’s equations describe how magnetic fields are related to electric fields and how they are generated by charges and currents. An extremely important result from Maxwell’s equations is that light itself is an electromagnetic wave, travelling through the electromagnetic field rather than requiring a material medium. This shows that fields are a not mathematical abstractions, but physically real entities capable of carrying energy and momentum through space.

Einsteins Theory of General Relativity

In 1915, Albert Einstein published his theory of General Relativity, which is the best theory of gravity we have developed. Earlier, we discussed Newton’s Theory of gravity, which raised the issue of action at a distance. We introduced a gravitational field as a solution to this problem, and later through Faraday’s experiments, we characterised fields as physical entities. However, in General Relativity, gravity is understood as the curvature of spacetime. Instead of a massive object influencing a gravitational field, the object curves the geometry of spacetime. Smaller object traveling in this curved spacetime would follow the straightest possible paths, called geodesics, which appear as an orbits from our frame of reference. General Relativity therefore lays down a new framework for gravity: rather than actions at a distance or a force field, gravity emerges from the curvature of the physical spacetime we inhabit.

However, we should not disregard fields as physical entities. Attempts to unify gravity and electromagnetism by describing both as curvature in a four-dimensional spacetime break down when a non-zero electromagnetic field can exist in flat spacetime. Nevertheless, the theoretical work of Theodor Kaluza and Oskar Klein showed that the electromagnetic field can be described as curvature in a five-dimensional spacetime.

Conclusion

To conclusion, the problem of action at a distance drove centuries of scientific exploration. Newton’s law of gravitation highlighted the problem but left it unexplained. Later, with the introduction of the potential and the concept of fields by Faraday and Maxwell, it became clear that forces propagate throught space rather acting instantaneously at a distance. Finally, Einstein’s theory of General Relativity provided a complete theory of gravity, in which gravitational effects arise from the curvature of physical spacetime rather than a force. Nevertheless, fields remain fundamental in modern physics. Particles themselves can be described as excitations in Quantum fields. Quantum Field Theory is the most accurate description of particle physics.